Paying for elections in North Carolina

We support our democracy when we adequately fund the administration of our elections

Free, fair, and safe elections are fundamental to the practice of our democracy. When we collectively fund our elections, we can make sure that all North Carolinians who are eligible to vote can participate without barriers and with confidence that their voices will be heard.

For too long, election administration has been underfunded. The result has been to depress voter turnout, reinforce barriers to the ballot box for Black, brown, and other people of color and people with disabilities, and undermine trust in the outcomes of elections. And while many have pointed to the critical role that early voting options, well-trained poll workers, and consistent voter education play in ensuring robust turnout and thus a more representative democracy, funding for election administration has been under scrutinized as the primary driver of whether those pathways to civic engagement are available in every community.

Underfunding election administration is another form of voter suppression that may not be intentional, but ultimately it leads to disparate experiences at the polls based on race and income, while it also reduces voter turnout and confidence.

Counties that spend more on elections can effectively boost the electoral voice and power of their residents. In North Carolina, where access to the ballot box for every person regardless of who they are or where they live has been under attack for more than a decade, the State Board of Election and the County Board of Elections in all 100 counties, which are primarily responsible for election administration, are not receiving the robust funding necessary to keep up with rising costs associated with elections. Worse, these deficits are exacerbated by constant changes to voting laws, recent cybersecurity threats and growing threats of violence. The good news is that looking at recent data, counties that spend more on election administration have been able to boost turnout compared with their neighbors that have spent less to make the ballot accessible.

To support the functioning of our democracy, it is critical that advocates and policymakers focus on the role that funding plays to ensure access to the ballot box and maintain the safety of elections. This BTC report provides an overview of the literature on election funding, analyzes North Carolina’s investment in election administration, and outlines the process and priorities for funding decisions.

Figure 1

NC counties that spend more on election administration boost their residents’ electoral power

Written by Tyler Daye, Common Cause NC

Greater elections funding is associated with higher voter turnout in North Carolina. When comparing county level election spending per voter with 2022 voter turnout statistics from the North Carolina State Board of Elections, Figure 1 shows on average that the more a county spent on elections per voter for the 22-23 fiscal year, the greater the likelihood that county had a higher voter turnout in 2022. More concretely, every $10 in additional funding per person is associated with a 3.4 percentage point increase.

Onslow County provides one of the most striking examples. Among the 83 counties that provided FY 2022-23 budget data, Onslow spent the least amount per voter, $11.98 less than the national average. Onslow County also had the worst voter turnout in the state. Only 37.25% of eligible residents in Onslow County voted in the 2022 general elections. This was well below the statewide turnout of about 51%.

The evidence clearly shows that counties with better funding are boosting the electoral voices of their residents.

Funding delivers the right to vote

Voting doesn’t happen by magic. It takes time, expertise, and infrastructure to deliver the franchise. Inadequate funding can block citizens from making their voices heard at the ballot box, perpetuate systemic exclusion from the vote for people of color, and undermine trust in representative democracy.

Funding smooths the path to voting in a host of ways, both during and between election cycles. Protecting the health and safety of voters and poll workers, avoiding long wait times and lines at polling places, streamlining the time-intensive and technology-dependent process of registering voters, and accurately counting votes are all goals that require sustained and adequate funding. Moreover, public funding can provide continuity to election administration by retaining skilled staff, maintaining operational and technological systems for elections, and providing for more comprehensive voter education and outreach strategies.1Kropf, Martha, JoEllen V. Pope, Mary Jo Shepherd, and Zachary Mohr. “Making Every Vote Count: The Important Role of Managerial Capacity in Achieving Better Election Administration Outcomes.” Public Administration Review 80, no. 5 (2020): 733–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13216. As one researcher noted in a study of long voting lines during the 2004 presidential election: “Administering elections requires ample resources. Administering them well requires even more.”2Highton B (2006) Long Lines, Voting Machine Availability, and Turnout: The Case of Franklin County, Ohio in the 2004 Presidential Election. PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (1): 65–68

Underfunded elections reinforce the power and influence of white voters

The strongest predictors of voter participation are the number of polling locations and the hours they are open.3Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Harvard University, Presentation by Christian Grose on September 30, 2022, accessed at: Strengthening Democracy with Dollars? How Funding Changes Administrators’ Behavior & Increases Voter Turnout | Ash Center (harvard.edu) Researchers have found evidence that variations in election funding by jurisdiction can reinforce racial inequities in the delivery of voting rights in the South.4Kropf M, Pope JV, Shepherd MJ, et al. (2020) Making Every Vote Count: The Important Role of Managerial Capacity in Achieving Better Election Administration Outcomes. Public Administration Review 80 (5): 733–742. Polling place consolidations driven by decreasing budgets have led to Black voters having to wait two times longer than white voters to cast their ballots.5Voting Rights Lab, July 2020. Polling Place Consolidation: Negative Impacts on Turnout and Equity, accessed at: Polling-Place-Consolidation-Negative-Impacts-on-Turnout-and-Equity.pdf (votingrightslab.org) Researchers have also found that voting infrastructure and processes have more challenges in Black communities and communities with low incomes.6Roman Pabayo, Erin Grinshteyn, Brian Steele, Daniel M. Cook, Peter Muennig, Sze Yan Liu, Natalie J. Shook. The relationship between voting restrictions and COVID-19 case and mortality rates between US counties, PLOS ONE 17, no.66 (Jun 2022): e0267738.

Adequate public funding can disrupt these inequities and ensure that the ballot box is accessible to all.7Clark A (2014) Investing in Electoral Management. In: Norris P, Frank R, Martinez I, Coma F (eds). Advancing Electoral Integrity. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.165–188 and Burden BC and Neiheisel JR (2013) Election Administration and the Pure Effect of Voter Registration on Turnout. Political Research Quarterly 66 (1): 77–90

Funding builds trust in the outcomes of elections

The importance of a well-funded, well-functioning election administration goes beyond the quality of the experience for individual voters. Well-funded election administration can advance confidence in our democracy and pathways to broader civic participation. Nationally, the funding of poll workers in particular can matter for confidence in election outcomes.8Burden, Barry C., and Jeffrey Milyo. 2015. “The Quantities and Qualities of Poll Workers.” Election Law Journal 14 (1): 38–46. Internationally, research into the relationship between election funding and the health of a democracy has found associations between smaller elections budgets and lower voter turnout but also with high levels of election manipulation, voting irregularities, and public dissatisfaction with political parties, legislatures, and governments.9Clark A (2019) The Cost of Democracy: The Determinants of Spending on the Public Administration of Elections. International Political Science Review 40 (3): 354–369.

Public dollars can fund accessible and effective elections

As we seek to strengthen our multi-racial democracy, robust and consistent funding is a critical tool. Consistent funding allows election officials to efficiently plan in advance to ensure that elections run smoothly and ensure voter access is expanded not reduced. Robust funding can adequately support the full range of needs and changing nature of the inputs to a safe and sound election, including modern technology and public health and safety measures. In states like North Carolina where election laws change nearly annually, funding is even more necessary to implement new rules and educate voters about what they need to do to access the ballot.

Efforts to quantify the cost of an election per voter in 2000 estimated the cost at $10 per voter, which when adjusted for inflation requires $17.82 per voter today with high inflation continuing to drive up costs.10Caltech/MIT Voting Technology Project, July 2001. Voting: What Is/ What Could Be. Accessed at: Voting - What Is, What Could Be (2001) (caltech.edu) Meanwhile, researchers working to capture the cost during the pandemic estimated roughly $5 billion to administer the national election, an amount that translates to $29.70/ voter.11Stewart III, Charles. “The Cost of Conducting Elections.” MIT Election Data & Science Lab, https://electionlab.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2022-05/TheCostofConductingElections-2022.pdf. Author’s calculation of per registered voters in the United States, 168 million, accessed at: Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2020 (census.gov) Importantly, these measures do not estimate what is needed to get to a fully accessible, adequately funded election, but they do provide a benchmark based on what states across the nation have spent.

Specific costs to administer elections contribute to two important goals for our democracy: an accessible, equitable electoral process and a credible, fair electoral outcome. Recommended funding levels to protect the fundamental right to vote have been determined based on past experiences or estimates of the costs of goods or services that are required for a given voter population or voting process. Costs can vary by more than the size of a voting population in a jurisdiction but also by the format and tools used at a given polling location or by the particular needs of voters (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Estimates of election costs with recommended levels as available

| Item | Cost | Recommended level |

| Optical scanners12Breitenbach, Sarah, March 2, 2016. Aging Voting Machines Cost Local, State Governments. Stateline Article: Pew Charitable Trust. Accessed at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/03/02/aging-voting-machines-cost-local-state-governments | $5,000 | One per polling place |

| Computerized voting machines13Breitenbach, Sarah, March 2, 2016. Aging Voting Machines Cost Local, State Governments. Stateline Article: Pew Charitable Trust. Accessed at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/03/02/aging-voting-machines-cost-local-state-governments | $2,000 to $3,000 | One per 250 to 300 voters |

| Ballot printing14Norden, Lawrence, Edgardo Cortes, Elizabeth Howard, Derek Tisler and Gowri Ramachandran. April 18, 2020. Estimated Costs of Covid-19 Election Resiliency Measures. Brennan Center, Accessed at: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/estimated-costs-covid-19-election-resiliency-measures | 24 cents to 35 cents per ballot | |

| Poll worker15Norden, Lawrence, Edgardo Cortes, Elizabeth Howard, Derek Tisler and Gowri Ramachandran. April 18, 2020. Estimated Costs of Covid-19 Election Resiliency Measures. Brennan Center, Accessed at: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/estimated-costs-covid-19-election-resiliency-measures | $200/day | One per 208 voters |

| Language interpretation | $700/day | Each precinct should provide interpretation in a county covered under Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act. |

| One week of early voting | 89 cents per registered voter | Researchers recommend at least two full weeks of early in-person voting before Election Day.16Kasdan, Diana, October 31, 2013. Early Voting: What works. Brennan Center, Accessed at: Early Voting: What Works | Brennan Center for Justice |

| Public health measures, including cleaning supplies and single-use pens | 51 cents per registered voter | |

| Public education | 88 cents per registered voter | Adequate levels are unclear, and some states are spending up to $2.52 on outreach and education. |

| Capacity testing of online information | $40,000 per state |

Sustained funding is needed even outside of election seasons

These costs represent the most visible aspects of election administration — the experience of voters and the community during the elections themselves. Yet there remain additional aspects of election administration in the lead-up to and follow-up from elections that require funding.

Facility rentals, office supplies, and storage of voting equipment and supplies are year-round expenses for election administration.17ACE Project, The Electoral Knowledge Network, Voting Operations, Equipment, Materials and Premises Costs, accessed at: Equipment, Materials and Premises Costs — (aceproject.org)

Staffing and training of election administration officials is critical to the planning, monitoring and evaluation of elections. Staff costs include salary and benefits as well as training to remain up to date on the latest systems and election law, and any travel reimbursement or allowances. Election Director roles have widely varying starting salaries from a low of $30,000 to a high of $126,000. In North Carolina, 37 counties had starting salaries below the Living Income Standard for that county.18DeHart-Davis, Leisha, May 23, 2022. County Salaries in North Carolina, 2022. Accessed at: County Salaries in North Carolina, 2022 | UNC School of Government The average salary paid to Election Directors in 2021 was $66,000.

Finally, emerging costs have been identified, including $300 million nationwide to keep poll workers safe given threats of violence.19Tisler, Derek and Lawrence Norden, May 3, 2022. Estimated Costs for Protecting Election Workers from Threats of Physical Violence. Brennan Center, Accessed at: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/estimated-costs-protecting-election-workers-threats-physical-violence?utm_source=Votebeat&utm_campaign=618cfd08a8-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_05_06_11_26_COPY_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d2e6ae1125-618cfd08a8-1297173965 An additional $316 million is estimated to be needed nationally for securing election processes from internal security threats.20Norden, Lawrence, Derek Tisler and Turquoise Baker, March 7, 2022. Methodology for Estimating Costs of Protecting Election Infrastructure Against Insider Threats. Brennan Center, Accessed at: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/methodology-estimated-costs-protecting-election-infrastructure-against

Taken together, these estimates of the costs to administer elections provide a baseline to assess if public funding protects the voter comprehensively.

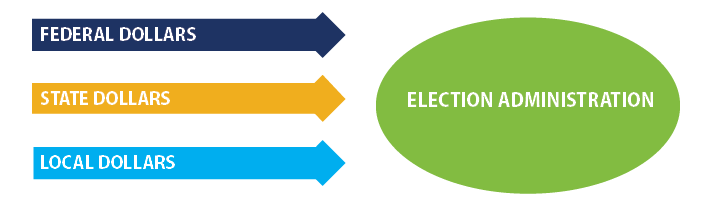

Figure 3: funding streams for election administration

The complicated web of election funding in North Carolina

Election funding can be hard to unpack given the combination of federal, state, and local funding streams, many with specific limitations or purposes. Challenges in gathering comparable data across jurisdictions further complicate research on the true cost of ensuring access to the ballot.21Zachary Mohr, Martha Kropf, JoEllen Pope, Mary Jo Shepherd, and Madison Esterle, “Election Administration Spending in Local Election Jurisdictions: Results from a Nationwide Data Collection Project,” paper presented at the annual meeting on Election Science, Reform, and Administration (ESRA), Madison, Wisconsin, July 26–27, 2018, https://esra. wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1556/2020/11/mohr.pdf. Budget documents can be difficult to access by the general public and when available are often presented in ways that are difficult to understand for the general public or don’t provide the level of detail that allows for full analysis.

Election administration is funded primarily at the local level by each county, with state and federal funding often providing limited, restricted, or inconsistent funding.

Inconsistent federal funding streams

Federal funds were first authorized by Congress for election administration after the 2000 elections. Subsequently, Congress established funding streams through grants to states and localities in the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) of 2002 with the primary grant programs “(1) making certain general improvements to election administration, (2) replacing lever and punch card voting systems, and (3) meeting the new requirements established by the act.”22Election Administration: Federal Grant Funding for States and Localities (fas.org)

HAVA funds originally required states to maintain the spending effort made in FY1999-2000 and continue to require a state match of 20 percent of the federal amount that the state is seeking to draw down for specific purposes. HAVA funds are not provided to the states every year. From 2010 to 2018, no new funds were made available by Congress to the states.

Once federal funds are provided to North Carolina, these dollars are held in a special fund and must be appropriated for use by the NC General Assembly in a given budget cycle. Due to the unpredictability of federal funding flows, federal funding has been spent over a longer time period than the fiscal year in which the funds arrived to ensure the sustainability of investments and to plan for purchases, such as voting machines, which are funded.23Bipartisan Policy Center, The Path of Federal Election Funding, accessed at: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/The-Path-of-Federal-Elections-Funding.pdf

Over time, additional grant programs have been established under HAVA, including ensuring access to polling places for people with disabilities, providing information about voting to young voters, recruiting poll workers, and improving access to the ballot for people living overseas.24Shanton, Karen L. October 5, 2022. “Election Administration: Federal Grant Funding for States and Localities,” Congressional Research Services, accessed at: Election Administration: Federal Grant Funding for States and Localities (fas.org) and Congressional Research Service in Focus, July 8, 2022. Election Security: States’ Spending of FY2018 and FY2020 HAVA Payments, accessed at: IF11356 (congress.gov)

Although numerous proposals to establish new federal funding streams have been introduced, few have been successfully approved — except during the COVID-19 pandemic. CARES Act funds were provided to states to support the presidential election by funding enhanced public safety measures, expanded mail-in and absentee voting options, and increased staffing.25US Election Assistance Commission, 2020 CARES ACT Grants, Accessed at: 2020 CARES Act Grants | U.S. Election Assistance Commission (eac.gov)

One additional federal funding source for election administration will come from a new requirement that 3 percent of the $2 billion in preparedness grants provided to localities by the US Department of Homeland Security must be spent on election security.26Department of Homeland Security, February 27, 2023. DHS Announces $2 Billion in Preparedness Grants, Accessed at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2023/02/27/dhs-announces-2-billion-preparedness-grants?utm_source=Votebeat&utm_campaign=618cfd08a8-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_05_06_11_26_COPY_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d2e6ae1125-618cfd08a8-1297173965 Election security practices identified include: “tamper-evident seals, security cameras, system testing before and after elections, audits, and physical and cybersecurity access controls.”27US Election Assistance Commission, Voter Equipment Security, accessed at: https://www.eac.gov/voters/election-security#:~:text=Common%20best%20practices%20include%20using,physical%20and%20cybersecurity%20access%20controls. This allocation of funding affirms a decision in 2017 by the US Department of Homeland Security that determined elections are critical infrastructure.

State funding for administration of elections is limited

State appropriations from the General Fund generally have been limited to the state’s funding of the Board of Elections’ staffing and operations that oversee elections as well as those that monitor campaign reporting and campaign finance ethics. These critical state functions that support elections in every county of North Carolina include maintaining voter files, tracking voter registration, and certifying election results.

Although the State Board of Elections is not required to fund localities for election operations, from time to time, state dollars are appropriated to be provided to counties. One instance in which General Fund revenue was provided to support counties directly was in 2008 when $1 million was allocated to fund the expansion of early voting sites.28Forsyth County Board of Commissioners Resolution, March 4, 2021, Accessed at: 5-21 (forsyth.nc.us) Another instance occurred in 2001 when state budget writers provided funds to support one-stop absentee voting sites in select counties.29Fiscal Research Division, NC General Assembly, 2001 Session. Overview: Fiscal and Budgetary Actions by the North Carolina General Assembly, accessed at: 2001 Overview Fiscal and Budgetary Highlights (ncleg.gov)

The State Board of Elections often administers funding that passes through to local jurisdictions and at times has the discretion to set the formulas that determine how funds will be allocated statewide. For example, the State Board of Elections allocated CARES Act funding in 2020 by using factors such as the size of the voting population and the measure of economic distress in the county.30Forsyth County Board of Commissioners Resolution, March 4, 2021, Accessed at: 5-21 (forsyth.nc.us) In so doing, the state Board of Elections recognized its opportunity to ensure that whether a county has its own resources to adequately fund elections should not determine voters’ experience at the polls.

Local election funding constrained by local capacity

Local Boards of Elections are primarily responsible for all aspects of election administration in North Carolina. To fund this year-round work that can be punctuated by multiple time-limited election events, Local Boards of Elections receive funding from the county Board of Commissioners as part of the annual budget process (see Figure 4. Election Funding Calendar). Local funding for elections often depends on the broader fiscal context in the community — its capacity to raise revenue and the impacts of broader economic trends like recessions — as well as the broader needs that must be met by a local budget.31Mohr, Zachary, JoEllen V. Pope, Mary Jo Shepherd, Martha Kropf, and Ahmad Hill. “Evaluating the Recessionary Impact on Election Administration Budgeting and Spending: Part of Special Symposium on Election Sciences.” American Politics Research, June 18, 2020. In North Carolina, decreased state funding to support public services has put pressure on local budgets serving to further hold down spending levels across many critical areas, including election administration.32Sirota, Alexandra, October 21, 2022. Early Voting has started in NC-how does funding affect your experience? Available at: NC Budget & Tax Center, https://ncbudget.org/early-voting-has-started-in-nc-how-does-funding-affect-your-experience/

Philanthropic funding streams helped meet costs of election

Funding from philanthropic organizations to support smooth elections in 2020 were a stopgap measure necessitated by the costs brought on by the pandemic and the lack of political will to provide adequate public funding.

This emergency funding provided much-needed poll worker capacity, protective masks, and even single-use pens, all key investments in keeping voters safe and elections secure. During the pandemic, 97 of 100 NC counties accepted philanthropic investment to make elections run smoothly in rural and urban counties, small and large.

Despite the importance of these dollars in meeting rising costs, legislatures nationwide and in North Carolina have sought to ban the funding of elections with private funds33Some Lawmakers Want Private Money Out Of Elections Administration | WUNC and Prohibiting Private Funding of Elections (ncsl.org) without addressing the underlying problem of chronic underfunding.

The latest push in North Carolina has come in the form of a policy provision in the NC House budget proposal. The proposal would ban the use of private funding sources by State and County Boards of Elections going forward.

As the Center for Tech and Civic Life noted in its final report on the COVID-19 Response Grants that provided more than $300 million to jurisdictions across the country:

“CTCL believes that election administration should be fully funded by federal, state, and local governments across the country, and the quality of election administration each voter receives should not depend on the tax base or size of their county.

“Philanthropy helped alleviate an emergency in 2020, and in ‘normal years’ it can help election offices build capacity, streamline processes, and make capital investments. But philanthropy is no substitute for predictable government funding.”34Final Report on 2020 COVID-19 Response Grant Program and CTCL 990s - Center for Tech and Civic Life

When state and local funding decisions are made

Voters and advocates need to understand when funding decisions that will shape their ability to make their voices heard at the ballot box are being made. Local election administration funding is part of the annual local budget process initiated by the county manager and decided by the county Board of Commissioners with input from the local Board of Elections and staff. The County Manager engages the Board of Elections in the fall to begin to identify budgetary needs. The local budget must be approved by the end of the fiscal year or June 30. Each new fiscal year begins July 1. While the process varies by local jurisdiction, the calendar for local budget development and passage follows a similar timeline as outlined in Figure 4.

Figure 4: election administration funding process is year-round

| July–Aug. | Budget implementation |

| Sept.–Nov. | Managers ask for budget requests for capital and operations |

| Dec.–Jan. | Analysis of projected financial position and county commissioners’ retreats for annual budget development |

| Feb.–April | Agencies and departments submit budgets |

| May | Budgets submitted to Board of Commissioners; public hearings begin; budget work sessions often start |

| By June 30 | Board of Commissioners adopts budget (by legal deadline) |

There are several opportunities for public engagement and for decisions to be made about the final budget, such as the number, location, and hours of operation for early voting sites and the pay for election administrators as well as poll workers.

Public engagement in the budget process has the potential to make funding more adequate given evidence that constituencies sharing their priority for a public service have often resulted in securing funding asks.35McGowan, Mary Jo, JoEllen V. Pope, Martha E. Kropf, and Zachary Mohr. “Guns or Butter ... or Elections? Understanding Intertemporal and Distributive Dimensions of Policy Choice through the Examination of Budgetary Tradeoffs at the Local Level.” Public Budgeting & Finance 41, no. 4 (2021): 3–19.

State and county funding falls short of the need

It is widely recognized that funding for election administration is often a low priority or overlooked in spending conversations and that funding levels fall far significantly short of the scale of need.36 Mohr, Zach, Martha Kropf, Mary Jo McGowan Shepherd, JoEllen Pope, and Madison Esterle. “How Much Are We Spending on Election Administration?” MIT Election Data & Science Lab, n.d., 2. At the state level, funding levels for election administration are falling behind the rising cost of goods and services and growth in the voting population. At the local level, funding remains noticeably low. In combination, these trends raise serious concerns that adequate funding is out of reach in order to protect North Carolina’s free and fair elections and to give voters confidence that their votes are properly counted.

Figure 5

There are two available ways to look at the funding of election administration at the state level.

One measure looks at the state’s effort to maintain election spending as required in the early years of the federal Help America Vote Act. North Carolina’s state dollars going to elections had to at least meet the threshold of $3.4 million based on the state funding levels for HAVA-covered activities in place during Fiscal Year 1999-2000. This maintenance of effort amount provides a bare minimum baseline for funding certain election administration activities — particularly related to voting systems — even though the US Election Assistance Commission has most recently determined that maintenance of effort is no longer required by law.

When current spending is looked at against this baseline, it shows that North Carolina’s funding effort has declined by 21 percent when adjusted for the cost of delivering these government services even as the agencies’ help-desk tickets have increased threefold just in the past decade. Again, while technically not in violation of federal law to fall short of this baseline, the goal to add to and not diminish the total funding commitment to elections has not been met.37Election Administration Commission, Final Maintenance of Expenditure Policy, Accessed at: Maintenance of Expenditure (eac.gov)

Another way to look at funding for election administration is to look at the state appropriation relative to the size of the voting population. As of early 2023, there are 7.3 million people registered to vote in North Carolina. As the number of registered voters in our state has increased, funding to the State Board of Elections has decreased when adjusted for the increased cost of delivering government services. The NC State Board of Elections budget for election administration, not including campaign finance and ethics reporting, has decreased by 19 percent between the 2007 and 2023 fiscal years; meanwhile, the number of registered voters in North Carolina has increased by 33 percent during the same period (see Figure 5).

In addition to singular measures, the most recent annual budget requests to the NC General Assembly and to Congress point to identified priorities that are going unmet under current state spending plans. In both instances, the need to adequately staff operations in technology and support services to County Boards of Elections were identified as critical needs given the volume of support requests and the broader context of threats. In addition, a specific, significant request for $13 million to support the upgrade of technology that all counties rely on for election administration was identified in the State Board of Elections’ request to the NC General Assembly for Fiscal Year 2023-2024.38North Carolina State Board of Elections, February 9, 2023. 2023-24 Budget Presentation.

Ongoing research will be necessary to fully assess the level of funding needed at the state level to provide the backbone of support to election administration statewide at a truly adequate level to the goal of an accessible ballot box for all eligible voters. In the meantime, the measures assessed here demonstrate that the state is not keeping up with key levels and areas of funding that prioritize access to the ballot box in complement to the heavy emphasis on election security from federal funding streams.

County funding for election administration is less than a penny of every $1 spent.39Sirota, Alexandra, November 2022. Early Voting has started in NC, how does funding affect your experience. NC Budget & Tax Center, accessed at: NC Budget & Tax Center

North Carolina requires local governments — and specifically counties — to fund election administration. Election administration funding across North Carolina’s counties has averaged less than 1 percent of county budgets over the past three elections. In the most recent budgets for the Fiscal Year 2022-23, Stokes County made the highest funding commitment as a share of the county budget, and Onslow County made the lowest.

As noted above, researchers’ most comprehensive review of election administration costs in 2000 found that administering an election averaged the equivalent of $17.82 per voter nationwide when adjusted for inflation. At a minimum, North Carolina counties should be reaching the national average in funding effort. Given the documented costs for funding elections during the pandemic, it is the bare minimum that our democracy can afford.

Analysis of the Fiscal Year 2022-23 county budgets available (Figure 6) shows that 18 counties met the recommended funding level and 64 fell short. Twenty counties did not have budget data available for their Board of Elections.

Figure 6

Photo IDs raise costs for voters and election administrators

Photo identification as a requirement to vote — as is being reheard in the state Supreme Court — would raise the costs for election administrators as well as voters.

When the photo voter ID proposal was being considered in 2018, various election administration costs associated with the implementation of strict voter identification laws included but were not limited to producing voter identification cards, conducting voter education and public outreach, revising and providing additional election materials, and training poll workers, as well as expanding staffing for election administration, IT infrastructure, and the processing of identification.40Sirota, Alexandra and Luis Toledo with William Munn and Patrick McHugh, September 2018. The Cost of Creating Barriers to Vote. BTC Report, NC Justice Center.

To implement a previous law requiring photo identification (H589) in North Carolina, the State Board of Elections spent upward of $3 million on voter outreach staff, printed materials for polling places and training, a paid media campaign, and related expenses.41Sirota, Alexandra and Luis Toledo with William Munn and Patrick McHugh, September 2018. The Cost of Creating Barriers to Vote. BTC Report, NC Justice Center. County election boards spent millions more, including printing their own materials and placing additional staff at each of the 3,000-plus Election Day and early voting polling sites to facilitate the administration of the law when it was in effect for the March 2016 primary. A fiscal note from the state’s Fiscal Research Division prior to the law’s passage estimated that the cost of staffing, printing, and otherwise delivering the creation of a “free” photo identification card would cost between $4.17 to $6.54 per registered voter who was without identification.42NC General Assembly, Fiscal Research Division, Fiscal Note House Bill 589. Accessed at: https://www.ncleg.net/Sessions/2013/ FiscalNotes/House/PDF/HFN0589v7.pdf. Researchers at the Fiscal Research Division did not estimate the cost of voter education or polling location costs nor did they capture the staffing costs at agencies beyond the Division of Motor Vehicles.

Even as the costs would rise for the state and counties should this requirement be implemented, the costs would rise too for individual North Carolinians, creating financial barriers in the form of fees for identification, travel costs, and lost time.

Conclusion

A budget is a reflection of our priorities as a community. The underfunding of election administration raises serious concerns about the commitment of our budget writers to delivering fair and free elections as the foundation of our democracy. Funding increases, particularly in the area of funding access to the ballot box, will be needed to uphold our democracy and the confidence that every vote will be counted and that every voice will be heard.

Footnotes

- 1Kropf, Martha, JoEllen V. Pope, Mary Jo Shepherd, and Zachary Mohr. “Making Every Vote Count: The Important Role of Managerial Capacity in Achieving Better Election Administration Outcomes.” Public Administration Review 80, no. 5 (2020): 733–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13216.

- 2Highton B (2006) Long Lines, Voting Machine Availability, and Turnout: The Case of Franklin County, Ohio in the 2004 Presidential Election. PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (1): 65–68

- 3Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Harvard University, Presentation by Christian Grose on September 30, 2022, accessed at: Strengthening Democracy with Dollars? How Funding Changes Administrators’ Behavior & Increases Voter Turnout | Ash Center (harvard.edu)

- 4Kropf M, Pope JV, Shepherd MJ, et al. (2020) Making Every Vote Count: The Important Role of Managerial Capacity in Achieving Better Election Administration Outcomes. Public Administration Review 80 (5): 733–742.

- 5Voting Rights Lab, July 2020. Polling Place Consolidation: Negative Impacts on Turnout and Equity, accessed at: Polling-Place-Consolidation-Negative-Impacts-on-Turnout-and-Equity.pdf (votingrightslab.org)

- 6Roman Pabayo, Erin Grinshteyn, Brian Steele, Daniel M. Cook, Peter Muennig, Sze Yan Liu, Natalie J. Shook. The relationship between voting restrictions and COVID-19 case and mortality rates between US counties, PLOS ONE 17, no.66 (Jun 2022): e0267738.

- 7Clark A (2014) Investing in Electoral Management. In: Norris P, Frank R, Martinez I, Coma F (eds). Advancing Electoral Integrity. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.165–188 and Burden BC and Neiheisel JR (2013) Election Administration and the Pure Effect of Voter Registration on Turnout. Political Research Quarterly 66 (1): 77–90

- 8Burden, Barry C., and Jeffrey Milyo. 2015. “The Quantities and Qualities of Poll Workers.” Election Law Journal 14 (1): 38–46.

- 9Clark A (2019) The Cost of Democracy: The Determinants of Spending on the Public Administration of Elections. International Political Science Review 40 (3): 354–369.

- 10Caltech/MIT Voting Technology Project, July 2001. Voting: What Is/ What Could Be. Accessed at: Voting - What Is, What Could Be (2001) (caltech.edu)

- 11Stewart III, Charles. “The Cost of Conducting Elections.” MIT Election Data & Science Lab, https://electionlab.mit.edu/sites/default/files/2022-05/TheCostofConductingElections-2022.pdf. Author’s calculation of per registered voters in the United States, 168 million, accessed at: Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2020 (census.gov)

- 12Breitenbach, Sarah, March 2, 2016. Aging Voting Machines Cost Local, State Governments. Stateline Article: Pew Charitable Trust. Accessed at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/03/02/aging-voting-machines-cost-local-state-governments

- 13Breitenbach, Sarah, March 2, 2016. Aging Voting Machines Cost Local, State Governments. Stateline Article: Pew Charitable Trust. Accessed at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2016/03/02/aging-voting-machines-cost-local-state-governments

- 14Norden, Lawrence, Edgardo Cortes, Elizabeth Howard, Derek Tisler and Gowri Ramachandran. April 18, 2020. Estimated Costs of Covid-19 Election Resiliency Measures. Brennan Center, Accessed at: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/estimated-costs-covid-19-election-resiliency-measures

- 15Norden, Lawrence, Edgardo Cortes, Elizabeth Howard, Derek Tisler and Gowri Ramachandran. April 18, 2020. Estimated Costs of Covid-19 Election Resiliency Measures. Brennan Center, Accessed at: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/estimated-costs-covid-19-election-resiliency-measures

- 16Kasdan, Diana, October 31, 2013. Early Voting: What works. Brennan Center, Accessed at: Early Voting: What Works | Brennan Center for Justice

- 17ACE Project, The Electoral Knowledge Network, Voting Operations, Equipment, Materials and Premises Costs, accessed at: Equipment, Materials and Premises Costs — (aceproject.org)

- 18DeHart-Davis, Leisha, May 23, 2022. County Salaries in North Carolina, 2022. Accessed at: County Salaries in North Carolina, 2022 | UNC School of Government

- 19Tisler, Derek and Lawrence Norden, May 3, 2022. Estimated Costs for Protecting Election Workers from Threats of Physical Violence. Brennan Center, Accessed at: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/estimated-costs-protecting-election-workers-threats-physical-violence?utm_source=Votebeat&utm_campaign=618cfd08a8-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_05_06_11_26_COPY_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d2e6ae1125-618cfd08a8-1297173965

- 20Norden, Lawrence, Derek Tisler and Turquoise Baker, March 7, 2022. Methodology for Estimating Costs of Protecting Election Infrastructure Against Insider Threats. Brennan Center, Accessed at: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/methodology-estimated-costs-protecting-election-infrastructure-against

- 21Zachary Mohr, Martha Kropf, JoEllen Pope, Mary Jo Shepherd, and Madison Esterle, “Election Administration Spending in Local Election Jurisdictions: Results from a Nationwide Data Collection Project,” paper presented at the annual meeting on Election Science, Reform, and Administration (ESRA), Madison, Wisconsin, July 26–27, 2018, https://esra. wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1556/2020/11/mohr.pdf.

- 22Election Administration: Federal Grant Funding for States and Localities (fas.org)

- 23Bipartisan Policy Center, The Path of Federal Election Funding, accessed at: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/The-Path-of-Federal-Elections-Funding.pdf

- 24Shanton, Karen L. October 5, 2022. “Election Administration: Federal Grant Funding for States and Localities,” Congressional Research Services, accessed at: Election Administration: Federal Grant Funding for States and Localities (fas.org) and Congressional Research Service in Focus, July 8, 2022. Election Security: States’ Spending of FY2018 and FY2020 HAVA Payments, accessed at: IF11356 (congress.gov)

- 25US Election Assistance Commission, 2020 CARES ACT Grants, Accessed at: 2020 CARES Act Grants | U.S. Election Assistance Commission (eac.gov)

- 26Department of Homeland Security, February 27, 2023. DHS Announces $2 Billion in Preparedness Grants, Accessed at: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2023/02/27/dhs-announces-2-billion-preparedness-grants?utm_source=Votebeat&utm_campaign=618cfd08a8-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_05_06_11_26_COPY_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d2e6ae1125-618cfd08a8-1297173965

- 27US Election Assistance Commission, Voter Equipment Security, accessed at: https://www.eac.gov/voters/election-security#:~:text=Common%20best%20practices%20include%20using,physical%20and%20cybersecurity%20access%20controls.

- 28Forsyth County Board of Commissioners Resolution, March 4, 2021, Accessed at: 5-21 (forsyth.nc.us)

- 29Fiscal Research Division, NC General Assembly, 2001 Session. Overview: Fiscal and Budgetary Actions by the North Carolina General Assembly, accessed at: 2001 Overview Fiscal and Budgetary Highlights (ncleg.gov)

- 30Forsyth County Board of Commissioners Resolution, March 4, 2021, Accessed at: 5-21 (forsyth.nc.us)

- 31Mohr, Zachary, JoEllen V. Pope, Mary Jo Shepherd, Martha Kropf, and Ahmad Hill. “Evaluating the Recessionary Impact on Election Administration Budgeting and Spending: Part of Special Symposium on Election Sciences.” American Politics Research, June 18, 2020.

- 32Sirota, Alexandra, October 21, 2022. Early Voting has started in NC-how does funding affect your experience? Available at: NC Budget & Tax Center, https://ncbudget.org/early-voting-has-started-in-nc-how-does-funding-affect-your-experience/

- 33Some Lawmakers Want Private Money Out Of Elections Administration | WUNC and Prohibiting Private Funding of Elections (ncsl.org)

- 34Final Report on 2020 COVID-19 Response Grant Program and CTCL 990s - Center for Tech and Civic Life

- 35McGowan, Mary Jo, JoEllen V. Pope, Martha E. Kropf, and Zachary Mohr. “Guns or Butter ... or Elections? Understanding Intertemporal and Distributive Dimensions of Policy Choice through the Examination of Budgetary Tradeoffs at the Local Level.” Public Budgeting & Finance 41, no. 4 (2021): 3–19.

- 36Mohr, Zach, Martha Kropf, Mary Jo McGowan Shepherd, JoEllen Pope, and Madison Esterle. “How Much Are We Spending on Election Administration?” MIT Election Data & Science Lab, n.d., 2.

- 37Election Administration Commission, Final Maintenance of Expenditure Policy, Accessed at: Maintenance of Expenditure (eac.gov)

- 38North Carolina State Board of Elections, February 9, 2023. 2023-24 Budget Presentation.

- 39Sirota, Alexandra, November 2022. Early Voting has started in NC, how does funding affect your experience. NC Budget & Tax Center, accessed at: NC Budget & Tax Center

- 40Sirota, Alexandra and Luis Toledo with William Munn and Patrick McHugh, September 2018. The Cost of Creating Barriers to Vote. BTC Report, NC Justice Center.

- 41Sirota, Alexandra and Luis Toledo with William Munn and Patrick McHugh, September 2018. The Cost of Creating Barriers to Vote. BTC Report, NC Justice Center.

- 42NC General Assembly, Fiscal Research Division, Fiscal Note House Bill 589. Accessed at: https://www.ncleg.net/Sessions/2013/ FiscalNotes/House/PDF/HFN0589v7.pdf. Researchers at the Fiscal Research Division did not estimate the cost of voter education or polling location costs nor did they capture the staffing costs at agencies beyond the Division of Motor Vehicles.