Inflation halts in July, but most working parents still can’t afford the cost of basic necessities

For the first time in a hot minute, we got a bit of good news about inflation Wednesday, Aug. 10.

Overall consumer prices in July held steady nationally compared to the month before for the first time since May of 2020. It’s a heartening sign for people struggling to make ends meet.

Annual inflation in the South Atlantic region for July (9.5%) has been running ahead of the national rate (8.5%), driven in part by a stronger than average employment recovery pushing up consumer demand. The biggest mover last month was gasoline, where the national price dripped down almost 8 percent from June to July. This drop was largely offset by continued increases in the cost of food and shelter, leaving the overall cost of consumer goods and services largely unchanged.

Good tidings though it was, Wednesday’s news doesn’t erase the run up in prices over the past few years, or decades of stagnate wages crushing the buying power of many working people. Both state and federal policy choices over the past few decades have made it easier for corporations to underpay workers and for rich people to amass unseemly fortunes, while failing to boost workers’ wages. All of that made inflation over the past few years so much more harmful because working people were already playing catch up.

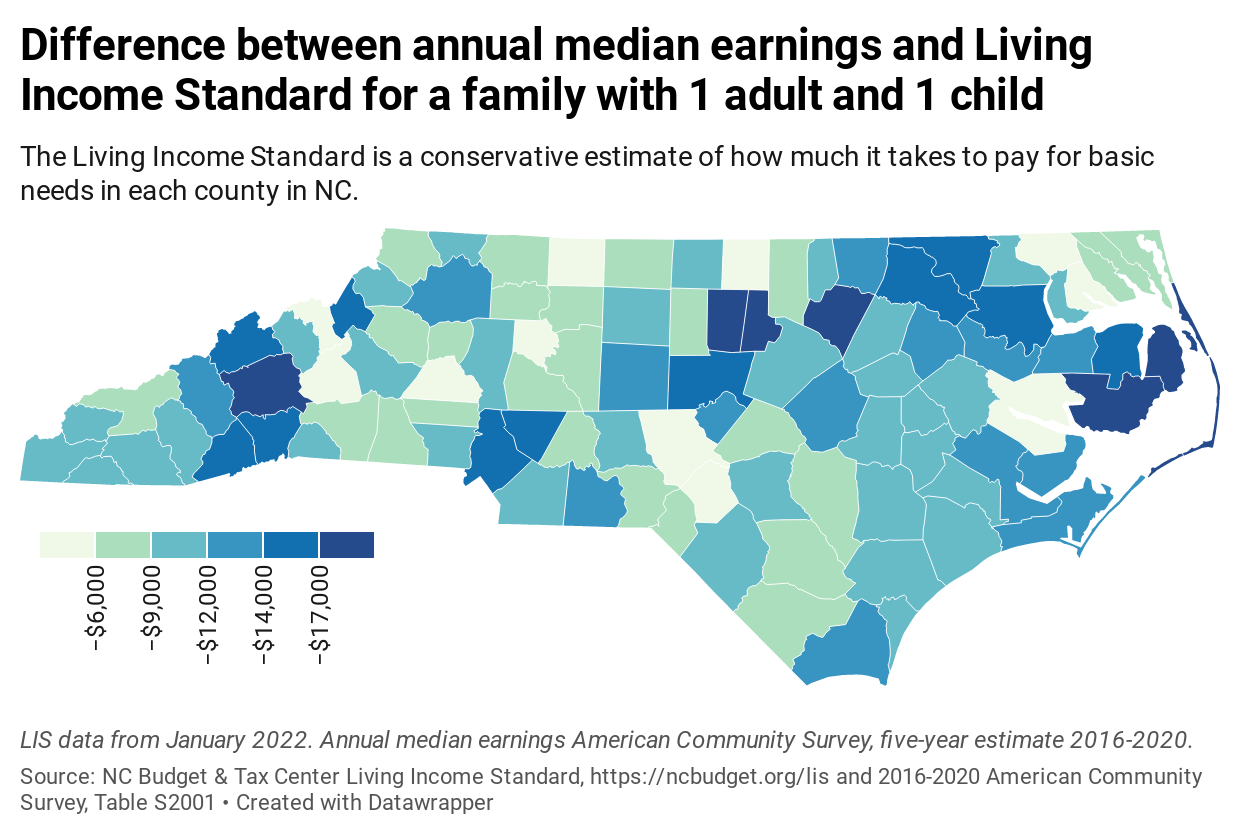

Given what things cost and what a typical worker earns in North Carolina, it’s hard or impossible for most parents to make ends meet without choosing which basic necessities to go without. Over the past few months, the Budget and Tax Center has released our Living Income Standard and Country Snapshots, which make it possible to compare what basic necessities cost to what a typical worker earns in all 100 North Carolina counties.

The results are striking.

A median worker’s earning do not cover the cost of basic necessities for a parent with one child in any of North Carolina’s counties. The gap between worker earnings and the cost of living tends to be widest for fastest growing metropolitan counties like Durham ($19,500), Buncombe ($18,000), Orange ($17,500), and Mecklenburg ($15,400), but the problem is not unique to these kinds of communities. Even in our most rural counties where the cost of living tends to be lower, median worker earnings are at least $5,000 a year short of what it takes to make ends meet.

While this analysis tells a compelling and urgent story, it can’t do justice to the many different realities facing working families across our state.

The wage data we’re relying on pre-dates the pandemic, and some parents have seen better earnings over the past few years. On the other hand, the Living Income Standard does not capture increasing costs since the start of 2022. We know wages have not been keeping up.

Another reality is the gap between median worker earnings and the Living Income Standard varies depending on how many parents can earn at that level. In most NC counties, a family with two parents collecting median worker earnings could bring in enough cover the cost of basic necessities, but that’s not true of families with one working parent or two working parents with three or more children. Two parents getting median worker earnings would fall more than $10,000 a year short of being able to provide for three kids in more than half of the counties in North Carolina. These kinds of differences aside, the consistent reality is the majority of families have a hard time making from one month to the next.

The Living Income Standard really could be called a “barely making it paycheck to paycheck standard” because it was intentionally designed to reflect an extremely modest standard of living. There’s no room for saving, putting a kid through college, buying a house, or a lot of what is rightly often associated economic security and comfort. Even the things that are in the standard are very conservative. Many of the people who looked at the cost of food we used from the US Department of Agriculture scoffed at the idea you could really feed a family on that kind of budget, particularly with the cost of food at home continuing to climb. All told, a family earning at this standard would be one lost job, one serious illness, one car breakdown, or one of any number of crises away from financial disaster.

Yesterday’s evidence of an inflation pause could be the start of something better, but we can’t lose sight of the long-term trends that make it so hard on working families. We can fight inflation and help working parents by forcing rich people and corporations to pay what they owe, support working peoples' power in bargaining with employers, reduce our dependence on volatile energy sources, and invest in making people and communities more productive. It’s all possible, and more needed now than before COVID-19.